Fundamentally there's a few ways to film into the darkness of an evening. Option 1, bring a lot of lights. Option 2, bypass the whole "visible spectrum" and go right into Infrared. That isn't to say Option 2 isn't without it's quirks. All of which presented an interesting learning curve when utilized on a project for a company that specializes in illuminating the darkness.

Our client asked myself and my creative partner to film a night 'live fire' rifle shoot using night vision, utilizing their own in-house night vision system. This client specifically creates IR aiming and illumination systems from individual soldier rifles, all the way up to crew-served machine guns. The advantage is that this allows us to give 1-to-1 feedback on how we think their night vision system can be improved from the standpoint of filmmakers.

The BE Meyers OWL night scope is fairly unique in a few regards:

- It utilizes C-Mount lenses

- It creates a non-vignetted image on full-frame sensors

Why the two aspects listed are important is that normal systems, for example the AN/PVS-14, is limited to 40 degrees of field of vision. Suffice it to say this isn't very helpful. The PVS-14 also has two modes of adjustment, either a front objective lens for focusing, or a diopter end for adjustment to the human eye. Things get a bit hairy when you have to adapt a system developed for fighting, to one for fun. This involves step up rings, adapted to a donor lens, so now you have 3 systems of focus to nail, an objective end, a back-focus end from the night observation device (referred to hereafter as a NOD), and finally the focus of the donor optic connected to the NOD.

Simply put...this is a mess. And is an absolute soup-sandwich for filmmaking.

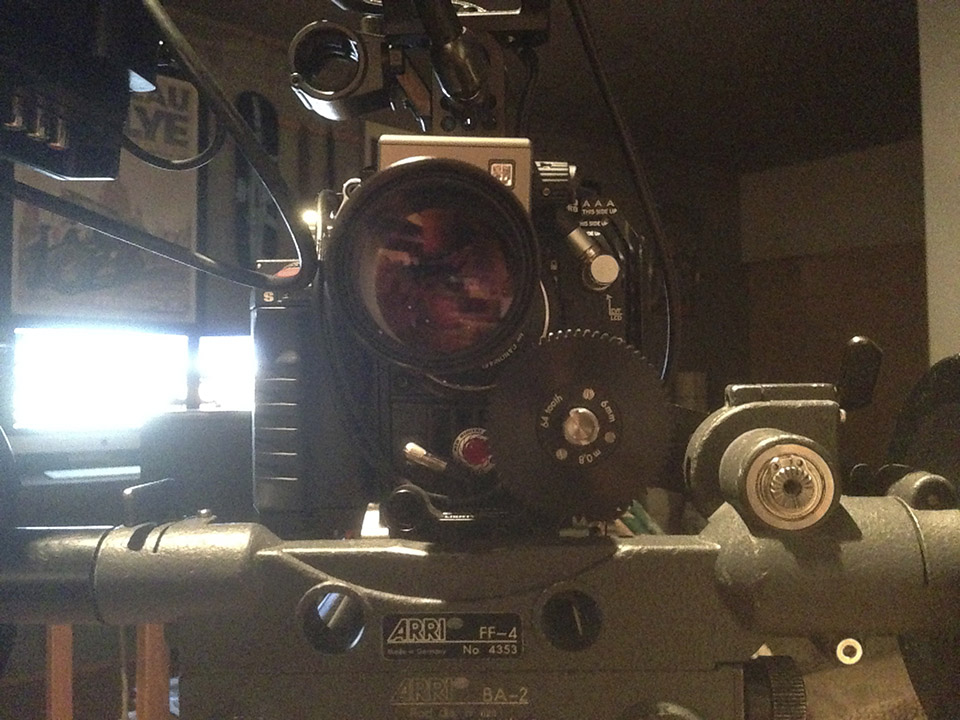

So when presented with the BE Meyers OWL we overcame a few problems right off the bat. First, we get the ability to interchange relatively low-cost lenses, with adjustable IRIS', repeatable and fixed focus system, and one step mounting. In the case of the OWL it was as simple as specifying that we wanted an Canon EF mount (swapping from PL and EF on the RED's side was as simple as removing 4 screws, swapping, and reinstalling).

Overall this means one system to achieve a desired result. As long as the back-focus of the OWL is set correctly this means that you can remove and reinstall reliably without any issues on the EPIC or Optic.

Example: 'Zero Dark Thirty' (ARRI Alexa + NOD)

Unfortunately we also learned a few downsides. The biggest being is that in this project's case we didn't learn till the night before that it used C-mounts, which while a pleasant surprise, wasn't a type of lens we had kicking around. So we were locked into the supplied 50mm. On the night of we simply rolled with the focal length we were dealt. But it does allow for intriguing future opportunities to source more C-mounts in shorter and longer focal lengths. C-mounts also tend to be fairly affordable and fast (this lens was an f/stop of 0.95).

The other technical issue is that it's all focus by hand. This means pulling focus or iris pulls becomes a fun game of guess work. A good quality NOD tube, the photo-electric plate that actually pulls light in and amplifies it a million times to a visible level, is running at about 600-800 lines per inch. This means you're essentially filming a barely 720p image through a 5K sensor, then outputed to a field monitor. As a result it's pretty tricky, but not impossible to get solid focus.

The C-mount lens is also un-geared, which prevented us from utilizing our ARRI Follow Focus, which in combination with a larger diameter focus wheel, would have made focus pulls less of a head scratcher. And because we only received our optic the night before, we weren't able to source any zip gears. After shooting that evening our hope is to see about either sourcing small enough zip gears, or having a set of delrin gears machined, and press-fit, on to the C-mount. This combination would essentially allow us to drive the lenses in the same manner as a normal DSLR or Cinema lens.

Another interesting facet of night production is that you're constrained to using either the natural moonlight (albeit amplified by a factor of a million) or additional infrared light. The OWL has it's own IR illuminator, but this amounts of an IR LED. As a result it tends to overexpose anything within a short throw of the OWL, without really getting the light where's it needed in the case of outdoor environments. Thankfully the products being filmed were incredibly powerful IR illuminators/designators, which meant that by essentially bouncing the light using one of these weapon-intended lights sources, we could kick additional IR light where we wanted.

Our schedule was fairly tight, and future testing would be nice to see how these IR illuminators would behave if used in conjunction with flags or reflectors. There's a whole world of possibilities we just didn't have time to test against. Next time for sure.

Example: PVS-14 + Canon 5DmkIII

Source: Roy Lin / Weapon Outfitters

None of these are really complaints, but rather areas I see as improvements to what is normally a very finicky proposition when using other systems (PVS-14). But the results are rather spectacular. The OWL doesn't create the typical 'image in a donut' effect that we normally associate with NODs hooked up to cameras (example: Patriot Games). Instead the OWL fills the entire frame with a glorious green image. As a result this gives us the option to later on add back vignetting if we're trying to simulate the point of view of a soldier seeing through a NOD. But for the purposes of a product video it's certainly a requirement not to waste half your image with just straight blackness.

At the end of the day, or rather night as this case may be, it's an interesting experience to eschew conventional optics and visible light, in favor of systems designed for the military. The results were exceptional, and combined with the RED Epic allowed us to get some shots typically not seen on video. We feel that our 36 hours with the OWL were short, but provided valuable take-aways that we can come back to, and improve on.